Part II: Feeling machines that think

Dr Kush Joshi

Co-founder and Sports and Exercise Medicine Consultant

In part 1, we discussed two problems with exercise: current guidelines assume we're all identical, and we ignore our emotional response before, during, and after exercise.

So how do we fix this?

We're not all identical. Individual biology plays a fundamental role in response to training that goes beyond genes. Sex, age, weight and baseline cardio-respiratory fitness, among other things, e.g. recovery, nutritional status and stress, affect our response to exercise.

Let's take an example from elite sport, my area of expertise, to demonstrate a solution. Kristian Blummenfelt and Gustav Iden are two Norwegian Triathletes at the top of the world rankings. They have the same coach, participate in the same races, train together, have the same goals, but have different training programs. Their coach, Olav Alexander Blu, uses in-lab testing, testing during a session and real-time athlete feedback to plan and adjust their training on the fly. Two athletes, same goals, different approaches, adapted in real-time: producing two individuals who can swim, bike and run the fastest in the world over a set distance.

This may seem unrelated to us mortals and our constant battle to not 'next episode in 10, 9, 8 seconds' on Netflix. Few want to swim a lake, bike 112 miles, and go straight into a marathon. But, most of us want to be fit enough to continue to do more of what we love: gardening, tennis, out-competing our 5-year-old at football or exploring the area on a family holiday.

Exercise physiology is part of an answer on how to do this for the elite triathlete and us normals.

In Kristian's and Gustav's case, in-lab physiology testing and real-time testing during a session help them understand their physiological thresholds, like lactate, ventilation and critical power, among others. Ignore the names; the basic principle is that understanding their physiology helps them manage volume, duration and intensity for planning training before a race season and on the fly during a session. It helps produce world-class athletes in swimming, biking, running, cross-country skiing and many other endurance sports. But what has this got to do with me?

Using physiological thresholds for exercise prescription has demonstrated excellent results in improving fitness in those struggling to respond to homogenous prescriptions driven by guidelines. This is useful for you and me. But, it's impractical to think many of us have the desire, time or money for in-lab and in-session testing.

However, inexpensive, practical and reliable self-assessed tools like rating of perceived exertion and the talk test show accessible technologies can be deployed at scale. Rating of perceived exertion has shown to correlate strongly with in-lab testing for physiological thresholds. Changes in these thresholds can be monitored in real-time using feedback given to your mobile phone. Guidance on volume, intensity and duration can then be individualised to you. The good news for many of us is that this intensity management can stop us from going too hard, which often leads to a lack of enjoyment, injury and giving up. This also matters for our second point, our emotional response to exercise…

Feeling machines that think

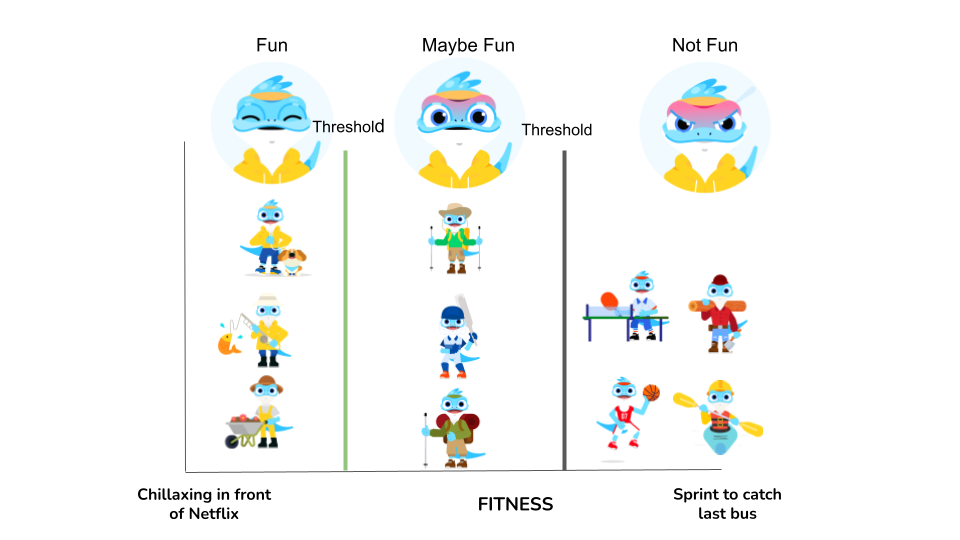

Why do the thresholds matter to how I feel and what I decide to do? Your thresholds above are related to how you feel during an activity. This is individual, and the impact is quite profound for many of the daily decisions we make and how we decide what we will do when it comes to any physical activity. To show this more concretely, here are two highly technical graphs I've put together to demonstrate the point:

Person A

Person B

Person A is a 40-odd-year-old non-gendered (gender doesn't matter for the example) individual who participated in some sport during childhood and into their late teens. During COVID, they started working from home. Besides gardening, childcare and walking around the shops, no physical activity occurred. Parties, work, and a family followed, and no structured exercise occurred.

Person B is the same 40-odd-year-old, but in a Sliding Doors twist of fate, they included some additional physical activity: weekend hiking, cycling to work, and a Judo class with the kids.

The graphs show two big differences: the capacity (the length of the fitness line) is greater in person B, and the thresholds (the vertical lines) are in different places.

This has implications. Person B has a wide range of activities that are at an enjoyable level of intensity. Their world of enjoyment is larger. Person A has fewer choices, and with no change, their world will get smaller and smaller. If Person A is a woman, by age 50, it won't be that much fun to play physical games with the kids, go for a walk in hilly countryside or do more than potter around the garden.

Now imagine person A decides enough is enough, and they'll get fit. Not knowing where to start, they go to the local gym and sign up for a circuit training class. Full body cardio and weights, what's not to like. They go the first time, it's scary, but everyone's friendly. Battling through the class, they spend the whole hour to the right of the graph in the 'not fun' zone. They're elated afterwards (it's over!), and then dread for the next session creeps in. Eventually, they quit and decide exercise isn't for them. They assign some cognitive failing - I'm not mentally tough enough. This needs to be corrected on so many levels. Sure, they may have increased their capacity (length of bottom line), but it's not fun. How could they do it differently?

Person A could choose activities below the first threshold line to get started. This may be brisk walking. Building up the volume at an enjoyable pace will push the first threshold further to the right and lengthen the bottom fitness line. More activities would now drop into the fun zone. Over time, they could periodically dip into the maybe fun or even the not fun zones for short periods to speed things up. Make those social like tennis lessons. Slowly but surely, their identity changes, and they view physical activity as enjoyable and part of their identity. But to do this, they need to understand the length of their fitness line and the thresholds. This is doable without expensive lab testing.

There's a lot you can learn from the images above:

Activities can be made discoverable based on your current fitness.

You can choose activities close to your first threshold that will help you get fitter and more likely to enjoy.

For any group activity (gym class, walking in the hills, running group), different people doing the same activity will have different physiological responses and emotional experiences.

Depending on what you want to be able to do, you can attack both the size of the fitness line and different thresholds.

No pain, no gain is wrong. There is a lot to be gained from working at lower, more enjoyable intensities.

We each have our own capacity (length of the fitness line in the images), our own thresholds and our own desires for activities we want to be able to do. And we want to have fun.

My hard sell

To make a dent and increase physical activity, we must move away from uniform prescriptions and provide free individualised self-assessment tools. And we need to stop telling people off and help them to have more fun. I'm dedicating my time to helping bring this to reality with Peezy. I'll keep you posted.